The London Dumping Regime – taking a lead in developing a legal framework for ocean fertilisation activities

Contracting Parties to the Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter 1972 (the London Convention) and the 1996 London Protocol have taken steps to address potential harm to the marine environment from the evaluation of new experimental technologies designed to reduce carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

In order to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement, large-scale extraction of carbon dioxide (CO2) seems imperative.

Mitigating climate change with ocean fertilisation

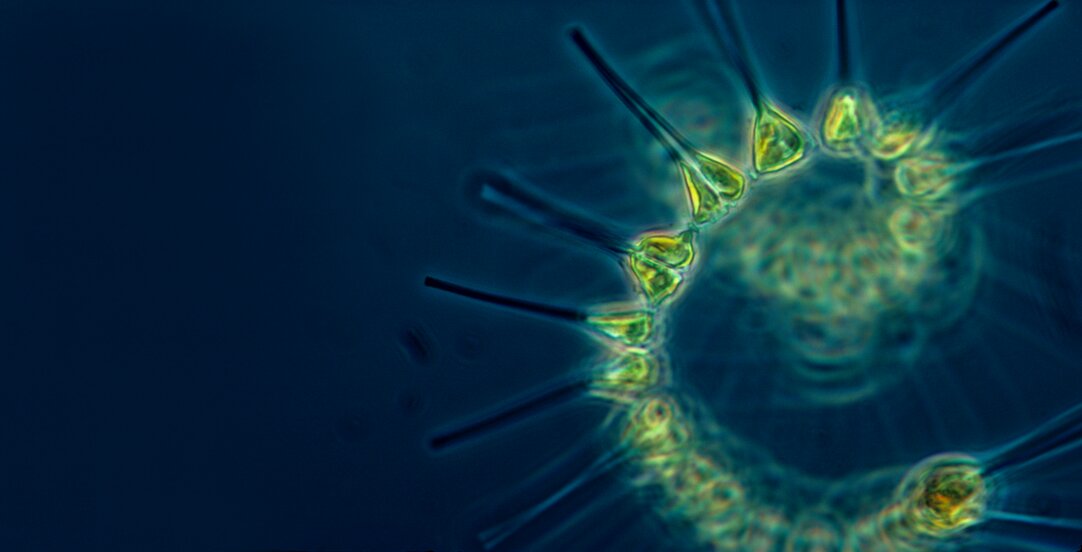

‘Ocean fertilisation’ refers to adding iron or other nutrients, such as volcanic ash, phosphate and urea, into the ocean in areas with low biological productivity in order to stimulate phytoplankton growth. In theory, the resulting phytoplankton draw down atmospheric CO2 and then die, falling to the ocean bed and sequestering carbon. Simply put, the objective of ocean fertilisation is to mitigate climate change by putting some of the carbon into a ‘hidden’ reservoir, where it cannot reach the atmosphere.

Lack of international regime for ocean fertilisation activities

From a legal perspective, there are many uncertainties in relation to ocean fertilisation activities. No international treaty regime or bodies are devoted to ocean fertilisation or geoengineering activities in general. That does not mean that ocean fertilisation takes place in a ‘legal black hole’. While the UN Climate Change Regime views ocean fertilisation as a mitigation measure, the Law of the Sea Regime (LOSC) categorises ocean fertilisation as pollution. The latter regime is the one setting the premises for the regulatory approach. As ocean fertilisation is an activity carried out in the ocean space and affecting the marine environment, it must adhere to the assigned limits of the LOSC Part XII obligations.

Regulating ocean fertilisation under the London Dumping Regime

The London Dumping Regime has taken a leading role in developing a legal framework for ocean fertilisation. Sparked by the increasing interest in this activity by both scientists and private operators, the contracting parties set about constructing a regulation on ocean fertilisation. Having confirmed their belief ‘that the scope of work of the London Convention and Protocol included ocean fertilisation’, in 2008 the contracting parties adopted ‘Resolution LC-LP. 1 (2008) On the Regulation of Ocean Fertilisation’. This resolution defined ocean fertilisation as ‘any activity undertaken by humans with the principle intention of stimulating primary productivity in the oceans’, and reaffirmed the belief that ocean fertilisation fell within the scope of the London Convention and Protocol. The 2008 resolution stated that ocean fertilisation for non-scientific purposes is subject to and contrary to the London Convention and Protocol.

Legitimate scientific research, by contrast, involves ‘placement of matter for a purpose other than mere disposal’ and may be permitted on a case-by-case basis if conducted in accordance with the Assessment Framework adopted by the contracting parties in 2010. Pursuant to this Framework, parties must undertake environmental assessments, emplace monitoring procedures and facilitate adaptive management. The Assessment Framework has been criticized for its scope and its content, inter alia for failing to provide incentives for the necessary scientific research on risk analysis by raising bureaucratic barriers to research experiments. Nevertheless, the Framework is described as a model of precautionary and adaptive management, offering both procedural and substantive environmental requirements. Neither the 2008 nor the 2010 resolution is legally binding, but a legally binding resolution to regulate ocean fertilisation was adopted in 2013. This resolution amends only the London Protocol, and adds a new Article 6bis:

Contracting Parties shall not allow the placement of matter into the sea from vessels, aircraft, platforms or other man-made structures at sea for marine geoengineering activities listed in Annex 4, unless the listing provides that the activity or the sub-category of an activity may be authorized under a permit.

A new Annex V adds the Assessment Framework for matter that may be considered for placement under Annex 4. The resolution stipulates that only ocean fertilisation activities ‘constituting legitimate scientific research taking into account [the] specific [2010] assessment framework’ can be considered for a permit. The amendments will enter into force sixty days after two thirds of forty-eight contracting parties have deposited instruments of acceptance of the amendment with IMO. That has not yet happened, as of the date of this SO Update.

Taking on a new role

By adopting a regulatory regime for ocean fertilisation activities, the London Dumping Regime has addressed a gap in the law of the sea and created a pre-emptive regulatory regime that endorses and implements a highly precautionary approach. This initiative under the London Dumping Regime is interesting because it demonstrates a wide interpretation of its mandate. From being a regime focusing primarily on protecting the marine environment from dumping (mainly from ships), the regime takes on a more active protective role and mandates itself as the appropriate forum for providing a global regulatory framework for geoengineering activities. However, there are practical problems with the London Dumping Regime taking on this regulatory role. The low endorsement of the London Protocol, and even lower endorsement of the amendment, make it difficult to argue that these regulations have become binding on all LOSC parties through the rule of reference included in LOSC Article 210. Another problem with the London Dumping Regime is the reliance on flag state jurisdiction. States have jurisdiction over ocean fertilisation activities in their maritime zones and over vessels and aircrafts flying their flag, which leaves ocean fertilisation activities on the high seas subject solely to flag-state jurisdiction.

Contributing to the Sustainable Development Goals

Ocean fertilisation has the potential to become a vital technology for achieving the emissions target in the Paris Agreement. This makes developing and applying ocean fertilisation techniques important in the context of the UN Agenda for Sustainable Development, especially in relation to Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 13, which urges action to combat climate change, and SDG 14, on ensuring sustainable use of the oceans. If overcoming the practical issues, the London Dumping Regime has the potential to offer a much-needed regulatory framework for ocean fertilisation activities.

For a longer and more detailed version of this article see: Elise Johansen, ‘Ocean fertilisation’ in E. Johansen, S.V. Busch and I.U. Jakobsen The Law of the Sea and Climate Change – Solutions or Constraints (Cambridge University Press, 2020).

-

Photo credit main image: NOAA MESA Project